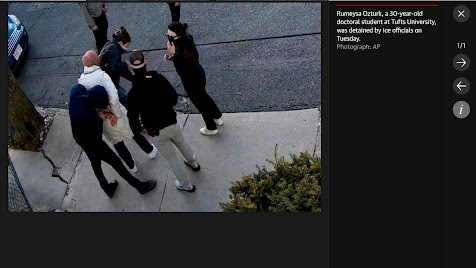

The Tufts University grad student kidnapped off the street by people in civilian clothing, wearing masks, to be shipped to a concentration camp in Louisiana - all without a warrant at the time she was seized this way.

|

| click the image to enlarge and read |

Yeah, they are not yet intentionally coming for me. But mistakes happen, as the Atlantic editor being invited to a top level Trumptsers chat over a military strike at another nation.

Or Musk overstepping and being judicially quelled. It is ongoing operations ripe for error, and if I of a sudden stop posting, please ask about it.

Concentration camps. Yes, what else to call it?

The LaSalle immigration court, inside a sprawling Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) detention centre in rural Jena, Louisiana, has been thrust into the spotlight in recent weeks after the former Columbia graduate student Mahmoud Khalil was transferred here earlier this month. His case has drawn international attention as the Trump administration attempts to deport the pro-Palestinian activist under rarely used executive provisions of US immigration law. The government is fighting vigorously to keep Khalil’s case in Louisiana and he is due to appear again at the LaSalle court for removal proceedings on 8 April.

But it has also renewed focus on the network of remote immigration detention centres that stretch between Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi, known as “Detention Alley” – where 14 of the country’s 20 largest detention centres are clustered. And now where other students have since been sent after being arrested thousands of miles away.

Badar Khan Suri, a research student at Georgetown University, was arrested in Virginia last week and sent to a detention centre in Alexandria, Louisiana, and then on to another site, Prairieland in eastern Texas. This week, Rumeysa Ozturk, a doctoral student at Tufts University, was arrested in Massachusetts and sent to the South Louisiana Ice processing centre in the swamplands of Evangeline parish.

These distant detention facilities and court systems have long been associated with rights violations, poor medical treatment and due process concerns, which advocates argue are only likely to intensify during the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown and promise to carry out mass deportations that has already led to a surge in the detention population. But rarely do cases within these centres attract much public attention or individual scrutiny.

“Most of the folks in detention in Louisiana aren’t the ones making the news,” said Andrew Perry, an immigrant rights attorney at the ACLU of Louisiana. “But they are experiencing similar, if not the same, treatment as those who are.”

To observe a snapshot of the more than 1,100 other detainees confined at the facility also holding Khalil, the Guardian travelled to Jena and witnessed a full day inside the LaSalle court, which is rarely visited by journalists. Dozens lined up for their short appearances before a judge and were sworn in en masse. Some expressed severe health concerns, others frustration over a lack of legal representation. Many had been transferred to the centre from states hundreds of miles away.

Earlier in the morning Wilfredo Espinoza, a migrant from Honduras, appeared before Judge Robbins for a procedural update on his asylum case that was due for a full hearing in May. Espinoza, who coughed throughout his appearance and had a small bandage on his face, had no lawyer and informed the court he wished to abandon his asylum application “because of my health”. The circumstances of his detention and timing and location of his arrest by Ice were not made clear in court.

He suffered from hypertension and fatty liver disease, he said through a Spanish translator. “I’ve had three issues with my heart here,” he said. “I don’t want to be here any more. I can’t be locked up for this long. I want to leave.”

The judge asked him repeatedly if he was entering his decision of his own free will. “Yes,” he said. “I just want to leave here as quickly as possible.”

The judge ordered his removal from the US.

Substantiated allegations of medical neglect have plagued the Jena facility for years. In 2018, the civil rights division of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) examined the circumstances of four fatalities at the facility, which is operated by the Geo Group, a private corrections company. All four deaths occurred between January 2016 and March 2017 and the DHS identified a pattern of delay in medical care, citing “failure of nursing staff to report abnormal vital signs”.

At the South Louisiana Ice processing centre, an all-female facility that is also operated by the Geo Group and where Ozturk is now being held, the ACLU of Louisiana recently filed a complaint to the DHS’s civil rights division alleging an array of rights violations. These included inadequate access to medical care, with the complaint stating: “Guards left detained people suffering from severe conditions like external bleeding, tremors, and sprained limbs unattended to, refusing them access to diagnostic care”.

The complaint was filed in December 2024, before the Trump administration moved to gut the DHS’s civil rights division earlier this month.

The spokesperson added: “These allegations are part of a longstanding, politically motivated, and radical campaign to abolish Ice and end federal immigration detention by attacking the federal government’s immigration facility contracts.”

The DHS did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Louisiana experienced a surge in immigration detention during the first Trump administration. At the end of 2016, the state had capacity for a little more than 2,000 immigrant detainees, which more than doubled within two years. A wave of new Ice detention centres opened in remote, rural locations often at facilities previously used as private prisons. The state now holds the second largest number of detained immigrants, behind only Texas. Almost 7,000 people were held as of February 2025 at nine facilities in Louisiana, all operated by private companies.

“It is this warehousing of immigrants in rural, isolated, ‘out of sight, of mind’ locations,” said Homero López, the legal director of Immigration Services and Legal Advocacy in Louisiana and a former appellate immigration judge. “It’s difficult on attorneys, on family members, on community support systems to even get to folks. And therefore it’s a lot easier on government to present their case. They can just bulldoze people through the process.”

At the LaSalle court this week, the Guardian observed detainees transferred from states as far away as Arizona, Florida and Tennessee. In an afternoon hearing, where 15 detainees made an application for bond, which would release them from custody and transfer their case to a court closer to home, only two were granted.

Cases heard from detention are far less likely to result in relief. At LaSalle, 78.6% of asylum cases are rejected, compared with the national average of 57.7%, according to the Trac immigration data project. In Judge Robbins’s court, 52% of asylum applicants appear without an attorney.

In the afternoon session, the court heard from Fernando Altamarino, a Mexican national, who was transferred to Jena from Panama City, Florida, more than 500 miles away. Altamarino had no criminal record, like almost 50% of immigrants currently detained by Ice. He had been arrested by agents about a month ago, after he received a traffic ticket following a minor car accident.

In a very dreary report, businessinsider.nl noted:

ICE says 29,675 people are in custody in detention centers across the US. Though the numbers have slowed, ICE is still carrying out thousands of deportations a month - 17,965 in March and 2,985 in the first 11 days of April, according to ICE spokeswoman Mary G. Houtmann.

Detainees allege ICE is rationing basic hygienic products and not giving them masks

Tiben said all but one of Pine Prairie's dormitories, which house up to 70 people, are under quarantine. Detainees cannot leave their rooms to exercise or go to the cafeteria, and meals are served in the dorm themselves.

Though they share every surface, the detainees have not been given masks, gloves, and other basic hygienic products, like hand sanitizer, disinfectant, or wipes, according to Tiben. Two detainees* told Business Insider that soap is rationed and given out every one to two weeks, which ICE spokesman Bryan D. Cox denied.

For-profit corporations run many detention centers, including Pine Prairie, which is managed by the private prison giant Geo Group.

A spokesperson for the Geo Group denied medical neglect in the facility and told Business Insider the detention center "provides access to regular handwashing with clean water and soap in all housing areas and throughout the facility."

An attorney suspects 'massive under-testing'

"You're going to see a loss of life" because of exposure to the coronavirus in ICE detention centers, Jeremy Jong, a Louisiana-based civil rights attorney, told Business Insider.

Alongside colleagues at the Center for Constitutional Rights, the National Immigration Project, and the Loyola Law Clinic, Jong has filed lawsuits in three states to try and free detainees with underlying medical conditions that make them more susceptible to COVID-19.

According to the ICE website, the agency has only carried out 1,030 coronavirus tests on detainees nationwide. Some 490, or 48%, have come back positive. Another 36 ICE employees at detention centers have tested positive, as well.

But Jong suspects the disease is much more widespread in detention facilities than what has been reported.

According to the ICE website, there only have been 20 confirmed cases at Pine Prairie, but Jong alleged that number is "the result of massive under-testing."

Cox said ICE will carry out 2,000 coronavirus tests per month, but that those tests will be earmarked "to determine detainee health and fitness for travel" - in other words, to clear migrants for deportation.

These are, at the most primitive level, human beings no different in that than Donald Trump, Usha Vance, us, or others - to be decently treated.